| 1. | ||

| 2. | ||

| 3. | ||

| 4. | ||

| 4.1. | ||

| 4.2. | ||

| 4.3. | ||

| 5. | ||

Analysis of B1 Listening Tasks in UPV CertAcles Certification Exams

Cristina Perez-Guillot

Applied Linguistic Department, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain

Email address

Citation

Cristina Perez-Guillot. Analysis of B1 Listening Tasks in UPV CertAcles Certification Exams. International Journal of Modern Education Research. Vol. 3, No. 4, 2016, pp. 20-27.

Abstract

Test tasks development needs to take into consideration not only the process from the point of view of applied linguistics but also the basis principles of language assessment and the framing of such principles within a model of linguistic competence. University-based language centres have made a great contribution to the development of language learning since their emergence and have played a major role in the development and implementation of language policies and language education. The function of language centres can be defined as the need for the development of more reliable systems for the accreditation or certification of language competence which will provide a basis for comparability of levels of assessment at European level. ACLES (The Spanish Association of Higher Education Language Centres) has recently launched a certification, called CertAcles based on a consensus among Spanish universities. The Language Centre (CDL) of the Universidad Politécnica de Valencia (UPV) has been closely involved and actively collaborating in the development of CertAcles certification scheme. In this paper I describe and analyse the different tasks developed for the CertAcles B1 listening paper as I have checked that it is the weakest skill for Spanish students. The results will be used for the design of more specific courses for the preparation of this kind of papers and as feedback for the exam developers.

Keywords

CEFR B1, ACLES, CertAcles, Listening, Tasks

1. Introduction

In the last two decades, higher education in Europe has undoubtedly undergone significant changes that involve new approaches in the teaching and learning of foreign languages. Student nunbers in higher education have increased considerably, the importance of English as a world language has escalated [11, 13] and academic and professional mobility has become the norm [26]. The creation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) has evidenced the need for the development of language policies at universities that support exchanges, networks and mutual learning recognition between schools, universities or training centres.

EALTA members involved in test development will clarify to themselves and appropriate stakeholders (teachers, students, the general public), and provide answers to the questions listed under the headings below. Furthermore, test developers are encouraged to engage in dialogue with decision makers in their institutions and ministries to ensure that decision makers are aware of both good and bad practice, in order to enhance the quality of assessment systems and practices.

Linking to the CEFR is a complex endeavour, which may often take the form of a project to be developed along a nunber of years. Linking exams or tests to a standard such as the CEFR requires a scientific approach, and claims must be based on the results of research, preferably submitted for peer review. Institutions/exam providers wishing to claim linkage to the CEFR are accountable for the provision of sufficient convincing evidence for such linkage. The following considerations may be useful to gather such evidence.

The European Confederation of Language Centres in Higher Education or CercleS [12] reached consensus on the core functions of a language centre. There are some authors which agreed that "there were three types of activity common to all language centres, whatever their name or institution framework and however diverse their missions" [1]. These were:

• Practical language training, especially for learners not specialising in languages,

• The use of appropriate technology for language learning,

• Research and development in the field of language teaching and learning.

However, in the most recent years a new function of language centres has become vital as university students need to prove their language competence at different stages and for many purposes such as mobility, graduating, entrance to master programmes, and so on [21].

This new function of language centres can be defined as the need for the development of more reliable systems for the accreditation or certification of language competence which will provide a basis for comparability of levels of assessment at European level, i.e. the standardisation of the different language competence levels according to the guidelines and descriptors of the CEFR and the homogenisation of the corresponding evaluation systems.

In Spain, the Association of Higher Education Language Centres (ACLES) was born in 2001. ACLES has recently launched a certification, called CertAcles based on a consensus about general aims and which has been approved by the national Committee of University Rectors (CRUE) and has gained national recognition in higher education institutions (CRUE 08/09/2011).

The CDL is currently involved in the development CertAcles exams in accordance with the model developed by ACLES for the English language that range from Basic User (A2) to Competent User (C1). The CDL offers two annual exam sittings of the Certification of Language Competence to be held in January and June after the period of regular academic exams of the courses of the student´s engineering degrees.

CertAcles exams measure the four skills –reading, writing, listening and speaking–and give equal weight to each section. They were officially recognised by the Spanish Conference of Rectors in 2011 (CRUE, 2011) and by the Regional Government in Valencia in 2013 (DOGV, 2013).

The CDL has a team of professionals who have been trained by renowned experts in test development and accreditation systems. But due to the fact the process of test development is a very costly one both in terms of time consumption and specific training of highly qualified personnel, as well as in economic terms, a detailed analysis of results is essential to provide reliable feedback to exam makers and thus help them improve the process of test design for future sittings.

In the present work I analyse the results obtained by the candidates in the paper of listening comprehension of CertAcles Certification Exam - Level B1 held in July 2013, following the same structure as the study developed for CertAcles B2 exam. The results of the analysis will serve to improve the process of test development as well as to design course contents and teaching materials particularly focused on those listening-comprehension aspects in which our students may need some extra remedial work.

2. Overview to Listening Comprehension

There is a direct relation between the basic principles of the linguistic assessment and tasks development, so it is essential to take them into account. Awareness of validity, reliability, practicality, authenticity and impact ensures the internal consistency of the tasks for the purpose for which they are developed while attending to the specific requirements of listening skills. These principles are also important when linking our tasks to the CEFR.

Approaches to assessing listening skills gradually evolved in tests such as PET and so did the process of test construct definition. As greater stress was placed on describing actual ability to use, and especially as technological solutions made it possible to systematically capture and relay more varied and more authentic types of listening material within the testing event, so the process of construct definition within test specification became increasingly sophisticated and explicit [28].

The construct of L2 listening proficiency involves the ability to process acoustic input in order to create a mental model or representation, which may then serve as the basis for some form of spoken or written response. Other mental processes, such as goal-setting and monitoring, combine with processes through which the language users make use of their linguistic resources and content knowledge to achieve comprehension.

It is important to keep in mind the listening activities we want to target and the behaviour of the listener, that is, the listening strategies that the listener is going to used to complete the tasks. Both activities need to be framed and strategies within scales in the common European framework to be able to determine the right level of the exam.

There are three dimensions – individual characteristics, external contextual factors, and internal cognitive processing –, which constitute three components of a ‘socio-cognitive framework’ for describing L2 listening ability. In this framework, the use of language in performing tasks is a social rather than purely linguistic phenomenon, in agreement with the CEFR’s perspective on language, which regards the language user or learner as ‘a social agent who needs to be able to perform certain actions in the language’ (North 2009: 359).

An important element when designing listening tasks is the listener’s purpose for listening. Richards (1983: 228) notes that listening purposes vary according to whether learners are involved in listening as a component of social interaction. Many authors assert that reliable assessment of the listening skill is difficult to achieve, due to issues with construct validity.

Several writers in the field have offered lists or taxonomies of general listening skills, sub-skills or strategies [7,25,32]. For example, Richards (1983: 228-230) developed a taxonomy of micro-skills involved in different types of listening, which should be considered by test developers when designing the listening comprehension tasks. Some of Richard’s micro-skills are:

• Ability to retain chunks of language of different lengths for short periods.

• Recognise the functions of stress and intonation to signal the information structure of utterances.

• Detect key words (i.e., those which identify topics and propositions).

• Ability to guess the meanings of words from the contexts in which they occur.

• Recognize grammatical word classes, major syntactic patterns and cohesive devices in spoken discourse.

• Ability to recognise or infer the communicative functions of utterances, according to situations, participants, goals.

• Use real world knowledge and experience to work out purposes, goals, settings, procedures and predict outcomes from events described.

• Detect such relations as main idea, supporting idea, given information, new information, generalization, exemplification.

• Process speech at different rates, as well as speech containing pauses, errors, corrections.

• Detect attitude of speaker toward subject matter.

Linking to the CEFR is a complex endeavour, which may often take the form of a project to be developed along a nunber of years. Linking exams or tests to a standard such as the CEFR requires a scientific approach, and claims must be based on the results of research, preferably submitted for peer review. Institutions/exam providers wishing to claim linkage to the CEFR are accountable for the provision of sufficient convincing evidence for such linkage. The following considerations may be useful to gather such evidence. Linking of a test to the CEFR cannot be valid unless the test that is the subject of the linking can demonstrate its internal validity. Remember that if the context it is not appropriate it won’t be more because the exam is linked to the CEFR.

In the assessment context, another significant dimension to take into consideration is the dimension of the evaluation criteria according to which performance on a test task is marked or scored, what Weir [32] refers to as scoring validity. In any listening test there invariably exists a close and interactive relationship between context, cognitive and scoring validity. Weir describes this interplay in the following way: ‘There is a symbiotic relationship between context- and theory-based validity and both are influenced by, and in turn influence, the criteria used for marking which are dealt with as part of scoring validity’ [32].

To ensure validity we should have enough nunber of items, be sure of item discrimination, limited freedom for candidates (although it means less validity), avoiding ambiguity in items, the instructions have to be very clear with an explicit format and the candidate should be familiarised with it. It is also important to provide stable administration conditions, objective corrections for items and finally assure training of ratters.

3. General Overview of UPV CertAcles Accreditation Exam: B1- Listening Paper

The Language Centre of the UPV is the official language accreditation unit at the university, which offers different exam periods for the university members to accredit their language competence, as approved by the UPV Governing body in a session held on the 14 April 2011.

The CertAcles Language Accreditation paper is an exam delivered at the Language Centre of the UPV. Whose main aim is to accredit the competence level in the English language of the candidates for Levels A2 to C1 of the CEFR.

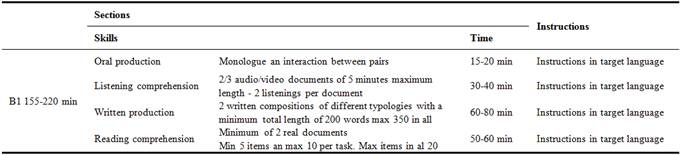

Table 1. Structure of the B1 LEVEL CertAcles Exam.

The contents and construct of the exam and the marking criteria are based on the CEFR descriptors. For that end the exam evaluates the four main communicative macro skills, i.e. Speaking, Listening, Writing and Reading, each with a specific weight of 25% of the total score of the exam. The exam is broken down into separate skills: oral comprehension, written comprehension, oral production and written production. In order to certify the overall performance, each of these four macro skills will be evaluated by examination.

A candidate is considered to have reached the corresponding language level if the final mark is equal to or higher than 60% of the total possible points, provided that a minimum of 50% of the possible mark has been attained in each skill. The marks are awarded on a scale of 0 to 10 points (100%) expressed to one decimal point:

• Between 6.0 and 6.9 points (60%-69% of total marks possible) = PASS.

• Between 7.0 and 8.9 points (70%-89% of total marks possible) = MERIT.

• Between 9.0 and 10 points (90%-100% of total marks possible) = DISTINCTION.

The CEFR describes what a learner is supposed to be able to do in reading, listening, speaking and writing at each level. More specifically, for the listening section corresponding to the B1 level, the CEFR establishes:

The ability to express oneself in a limited way in familiar situations and to deal in a general way with nonroutine information (Common European framework of reference for languages: learning, teaching, assessment: 27).

In the Guide of the candidate for the UPV CertAcles Certification test – Level B1 published in the website of the Language centre (Guía del candidato, CDL 2013), the CEFR descriptors corresponding to the listening comprehension section of the paper can be summarised as follows:

The candidate …

• Can understand the main words of a clear standard speech on familiar matters regularly encountered in work, school, etc.

• Can understand the main point of many radio or TV programmes on current affairs or topics or professional interest when. the delivery is relatively slow and..

• The first feature is the ability to maintain interaction and get across what you want to, in a range of contexts, for example: generally follow the main points of extended discussion around him/her, provided speech is clearly articulated in standard dialect

• The second feature is the ability to cope flexibly with problems in everyday life., for example cope with less routine situations on public transport; deal with most situations likely to arise when making travel arrangements through an agent or when actually travelling; enter unprepared into conversations on familiar topics; make a complaint;

This section of the exam consists of 3 audio documents to be listened twice, and the total duration is 30 to 40 minutes in all. The documents can include face-to-face conversations, broadcast interviews, and complex academic and professional presentations. The register of the audio documents can belong to native speakers with some local accent as well as to non-native speakers.

Regarding the layout of the tasks, before listening the candidates have 30 seconds to read the instructions and questions, they have to follow the instructions, which have been also recorded and answer while listening; at the end of each task, candidates have 15 seconds to check their answers.

Among the different types of tasks used to evaluate listening comprehension, we can mention the following: fill-in the gaps, open answer with limited nunber of words, multiple choice, true or false with justification, multiple matching, ordering, information transfer…

The following paragraphs describe the B1 listening-comprehension tasks of the CertAcles Certification paper administered in July 2013, and analyse the candidates’ results in each of the tasks and their overall performance. The reason for analyzing this section of the exam is because this is the skill where candidates showed most difficulties and poorer performance, [22] "candidates considered the listening section to be the most difficult, closely followed by the speaking section".

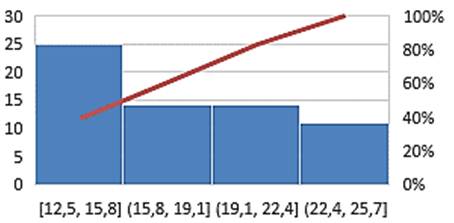

As we can see in figure 1 the listening paper is the one in which candidates have obtained the worse results. As we can observe the listening paper is the one in which candidates obtained worse results the average mark is 14,90 over 25. The reading paper as we can observe is the one with better results the average mark is over 20 points, followed by the results on the writing paper where 17 is the average points obtained by the candidates, quite similar results can be observed on the speaking paper where the average mark is 16 points.

Figure 1. Percentage of passing candidates per communicative skill.

4. Listening Comprehension Task Analysis

Before focusing in our main objective, which is to present the analysis of the results of the listening comprehension tasks, the results of the exam focusing in listening and speaking tasks will be revised. We would like to highlight that even though they are considered by the candidates much more difficult than reading and writing skills. The results show that their performance is no so bad as only 9% of the candidates fail the exam because of the listening paper, as it is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Listening results.

If we considered both listening and speaking skills figure 3 illustrates that only 6% of the candidates do not pass the exam due to their marks in both exams.

Figure 3. Listening & Speaking results.

In the B1 exam which have been analyzed in the present work, the tasks corresponding to the Listening Comprehension paper were three as follows:

TASK 1

• Task topic: summer holidays.

• Task type & format: Sentence completion. Candidates produce written answers by completing gapped sentences in a maximum of FOUR words answer and a total of 6 items.

• Task focus: In this particular case, the task served to test the candidates’ ability to listen for opinion and attitude, expressed in gist, main idea, and specific information.

TASK 2

• Task topic: Task nunber 2 is about spending less money on entertainment

• Task type & format: Sentence completion. Candidates produce written answers by completing gapped sentences in a maximum of three words. This task consists of 8 items

• Task focus: This part tests candidates’ ability to listen for specific words or phrases from a single long text, focusing on detail, specific information and stated opinion.

TASK 3

• Task topic: an interview with Alan Gillard, slimmer of the year 2007.

• Task type & format: It is a multiple choice activity. There are six questions and 3 options per item.

• Task focus: The task focuses on listening for general gist, detail, function, purpose, attitude, opinion, relationship, topic, place, situation, genre, agreement, etc. Candidates need to choose the right answer from three options A, B or C.

According to Buck (2011), ‘A variety of listening sub-skills may be assessed in multiple choice tests’. The test of listening sub-skills can range from "understanding at the most explicit literal level, making pragmatic inferences, and understanding implicit meanings to summarizing or synthesizing extensive sections of tests’. Each kind of listening sub-skill places a certain sort of demand on the test-takers.

Now the different results obtained by candidates in each of the tasks are presented, and then we will make a comparison between the results of all of them. Our goal will be to determine if there is any type of task that is more complex for the students and how these factors affect the students’ performance on their final mark.

4.1. Analysis of Task 1

Task 1 consists consisted of 6 items in which the candidates had to complete sentences with specific information using no more than four words.

As we can see in the graph (Figure 4), the majority of candidates obtained half of the possible points, that is, 26 candidates obtained 3 points followed by 33 who obtained 2 points and 21 who obtained 4 points, representing a total of 80 candidates in mean values (50.3%). So we can say that this task has been quite easy for the majority of the candidates who have got quite good results.

Figure 4. Analysis of task 1.

The extreme values are achieved by a similar nunber of candidates, with a total of 20 who got only 1 out of 6 points and 18 who obtained 5 out of 6. Finally, we have 15 candidates who obtained the maximum mark 6 points, with, and 6 candidates who did not get any point.

4.2. Analysis of Task 2

Task 2 is a sentence complexion activity in which the candidates can get a score between 0 and 8. The results show that 33 candidates obtained at least 4 points whereas 19 candidates obtained 6 points and 17 candidates obtained 5 points, so there are 69 (49%) candidates above the average.

It is worth noting that of these 69 candidates, more than half (36 candidates) who got 8 points (55.9%). On the other hand, the nunber of students who scored below the mean value of 4 points are distributed as follows: 14 candidates scored 3 points, 7 candidates scored only 2 points, 3 candidates just got 1 point and 2 candidates did get 0 points in this task.

Figure 5. Analysis of Task 2.

We can say that this task is quite easy because a large nunber of candidates were able to give right answers. It is clear that the typology of the exercise, in this case, complete sentences and short interview, where the message is easier to understand, allow the candidates to obtain better results. But we can observe that a long listening with just one topic is much easier than 5 different short extracts, because the results of the candidates are slightly better in the former one.

4.3. Analysis of Task 3

This task consists of a multiple-choice exercise with six items. We can see that of a total of 139 candidates, more than half (66.9%) obtained more than 3 points, of whom 26 obtained 3 points and 21 candidates got 4 points. We can also observe that the nunber of candidates with 5 are 18 meanwhile the ones with 2 points are much more 33 so we can consider the level of difficulty of the task.

It is also important to note that very few candidates obtained the maximum and minimum possible points, with a total of 20 who scored only 1 point and 6 candidates scored 0, whereas 15 candidates obtained the highest score of 6 points.

With these data we can consider that this task is within the expected results and if we add the candidates who have obtained 3, 4 and 5 points we observe that there are 80 (60.5%) out of 139 candidates.

Figure 6. Analysis of Task 3.

After this analysis, we can confirm that task type has a direct effect on the results of the candidates, that is to say Task 1 and 2 consisting of a sentence-completion activity are much more difficult for the candidates results indicating a similar level of difficulty. While Task 3, multiple choice provides better results

Thus, for practical purposes we can conclude that those tasks involving production present more problems as they require different mental processes. Tasks 1 and 2 imply summarizing, rephrasing, etc whereas the listening tasks that only involved recognition where performed better by the candidates, which indicates that recognising information is an easier mental process for candidates, independently of task type.

Figure 7. Comparison analysis of the 3 B1 Listening Comprehension tasks.

5. Conclusions

Figure 8. Listening results.

There are many different factors that need to be taken into account when developing and validating tests of academic listening ability.

According to the results, we can conclude that the minimum nunber of tasks to include in the Listening Comprehension section of the exam is at least three different ones to get a reliable measurement of the candidate’s ability to understand and process different types of information.

Task layout and format were also found to be closely related to the candidate’s results. The instructions and directions to complete the activities should be formulated as clearly as possible, using vocabulary and grammar patterns of a lower level than that evaluated in the exam.

We would like to highlight that the real purpose of the task is evaluating listening comprehension rather than reading comprehension skills. Similarly, a neat and well-organized visual presentation of the items in the task will help candidates concentrate on the aspects under evaluation, avoiding any distracting factors caused by a poor design of the task layout.

In our particular case study, we can also associate the better results of the receptive task with task layout and format. As in task 3 where the candidates have to identify the information worded in a simpler way than in the aural document, whereas the productive task (Tasks 1&2) demands from the candidate not only to recognize the required information but also to express it with a maximum of four or three words, which involves an additional mental process.

The findings of the present work helped us improve our regular course contents, in particular those aspects related to the listening comprehension B1 courses.

The analysis of test results is considered a key factor for the development of a more reliable system for the accreditation or certification of language competence. We hope that this paper will provide helpful insights for all who face the challenge of designing listening tasks and that our experience will contribute to ‘assessment literacy’, that is, to a better understanding of the complex factors and challenges involved in assessment, particularly the testing of B1 level listening skills.

Finally, the results were also used to improve test development, particularly those factors related to test layout, formulation of instructions and test design to avoid external factors from affecting candidates´ performance.

In conclusion, designing an exam is like maintaining complex machinery, all pieces need to work together and need to be maintained for the machine to complete its purpose. By taking into account the basic principles of language assessment and being familiarized with the CEFR we create valid exams that will be valid.

Figure 9. Conclusions.

References