Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Concerning Nutritional Care Support among Iraqi Health Care Providers

Muhannad R. M. Salih

Department of Pharmacy, Al-Rasheed University College, Baghdad, Iraq

Email address

Citation

Muhannad R. M. Salih. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Concerning Nutritional Care Support among Iraqi Health Care Providers. American Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. Vol. 3, No. 5, 2016, pp. 46-52.

Abstract

Malnutrition can be recognized as one of the main issues in clinical practice. It can be overcome by suitable nutrition care provided by the available clinicians. Nevertheless, this practice is still missing perhaps because of the insufficient providers’ knowledge. The study goal was to assess the pharmacists and the doctors self-reported practices, attitudes, and knowledge to nutritional care support in Baghdad Medical City. A cross-sectional study was done from February to March 2015 in Baghdad Medical City hospitals. The research tool (i.e., questionnaire) was distributed to 300 pharmacists and doctors employed in these hospitals using a drop-and-collect method. Of 102 respondents, 44 pharmacists and 58 doctors from different positions filled the questionnaire. Comparable proportion of pharmacists (29.1%) and doctors (31%) stated sufficient knowledge to do patient’s nutrition screening. In terms of knowledge score, doctors got higher mean score (5.37 ± 1.37) than what pharmacist had (4.70 ± 1.26, P=0.016), and more than three-quarter of them (80.4%) were congregated in the" average" score group. Furthermore, both doctor and pharmacists show unclear attitudes to nutritional care support. A considerable proportion of the respondents (42.2%) claimed that they made nutritional assessment throughout the patients’ hospitalization, and merely 38.2% of them reported that they do nutritional screening on admission. The lack of good or satisfactory level of nutritional care can be attributed to the absence of practical guidelines and inadequate knowledge among health care provider. Engaging both doctors and pharmacists in extensive educational and clinical training programs about nutritional care support could be worthy.

Keywords

Nutrition Support, Knowledge, Attitude, Practice

1. Introduction

Nutritionally-related health patterns in the Middle East have changed significantly during the last two decades. The main forces that have contributed to these changes are the rapid changes in the demographic characteristics of the region, speedy urbanization, and social development [1]. The low child malnutrition rate (19%) in the Middle East region is suggesting that nutrition insecurity remains a problem due mainly to poor health care and not due to inadequate dietary energy supply or poverty [2]. The one extreme country, Afghanistan, has a very high dietary energy deficit of 40% malnutrition rate. Likewise, Iran and Egypt have relatively high malnutrition rates of 39% and 16%, respectively. On the other hand, Morocco and the United Arab Emirates have the lowest malnutrition rates of 6% and 8%, respectively [3].By the same token, studies from European developed countries like Germany and England also highlight the risk of malnutrition with a prevalence rate of 20%–50% among hospitalized patients [4-6].

Nutrition screening has been defined by the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) as "a process to identify an individual who is malnourished or who is at risk for malnutrition to determine if a detailed nutrition assessment is indicated" [7]. In an effort to enhance nutritional care in the clinical setting, the European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) has founded a number of guidelines. These guidelines emphasize on the screening of all patients at the hospital admission time as well as to provide a nutritional care plan if the patient is at possibility of malnutrition [8]. While the popularity of under-nutrition in the free living population is quite low, the malnutrition risk radically increases in the hospitalized and institutionalized elderly subjects [9]. The malnutrition prevalence in cognitively impaired patients is even higher and is linked with cognitive decline [10]. Malnourished individuals who are admitted to the hospital tend to have higher length of hospital stay, greater morbidity and mortality risks, and experience more complications than those whose nutritional state is normal [11]. By identifying those malnourished individuals or those who are at risk of under-nutrition either in the community or hospital setting will allows health care providers to interfere earlier to deliver sufficient nutritional care support, avoid further worsening, and improve patient clinical outcomes [12].

The evidence base for the practice of curative and/or preventive nutritional care support is rapidly developing and research application progressively enhances delivery of good services. There is some doubt that clinicians might be more efficient in their routine regular practice when they rely on up-to-date nutritional clinical knowledge and effective practical skills [13]. Likewise, there are several instances of favorable patient clinical outcomes resulting from nutritional care practices in community, inpatient, and outpatient settings. In the same way, improvement in patient outcomes and reduction in health care costs were found to be significantly correlated to the quality of nutrition practice [14]. Notwithstanding the considerable positive nutritional effect on health and wellness, the nutrition science and its application to medical staff are not completely incorporated in most clinical training programs [15]. In majority of the published researches on attitude and knowledge concerning nutritional care support, pharmacists were received a less attention compared with other health care providers like dietitians, nurses, and doctors [16-21].

It was well-known that pharmacists is an important element in the nutritional care support team. They have been involved in several activities including patients’ nutritional assessment, clinical route monitoring, parenteral nutrition (PN) admixture, and evaluation of drug-nutrients interactions [22,23].

Up to the present time, in Iraq, the appropriate practice of nutrition support still missing perhaps due to the insufficient providers’ knowledge. However, there are no published studies demonstrate the actual issues as well as the challenges in the real situation. In view of that, the study goal was to assess the pharmacists and the doctors self-reported practices, attitudes, and knowledge to nutritional care support in Baghdad Medical City.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was done from February to March 2015 in Baghdad Medical City that include Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Specialist Hospital of Burns, and Private Nursing Home Hospital in Baghdad, Iraq.

The research tool (i.e., questionnaire) was distributed to 300 pharmacists and doctors employing in these hospitals. This was performed through a drop-and-collect approach in a period of one week. The non-respondents were given another week in an effort to enhance the response rate. Subsequently to the intentional end of data gathering, a reminder was given to motivate the non-respondents to fill the questionnaire. This study was approved by the Directorate of Baghdad Medical City, Ministry of Health-Iraq.

2.1. Study Tool

A four-division questionnaire with 32 questions was adopted for this study. This questionnaire was taken from previously validated published research [16]. The first division included questions on respondents’ demographics. The health care provider (i.e., doctors and pharmacists) were asked for their designation, year of starting service, gender, and age. The second and the third divisions does contain questions focusing on the practice and attitude of both pharmacists and doctors to nutritional care support thorough a five-point Likert-type scale answers. With respect to the attitude division, the respondents were assigned as "positive attitude" and as "ambivalence attitude" with a score range of 7–13 and 14–20, respectively. While the score of 21–28 was titled as "negative attitude". Ambivalence was described as the condition of owing mixed attitudes (negative and positive) or self-contradictory thoughts toward something.

Knowledge was the attention of the last division. It included multiple-choice questions to assess the respondents’ knowledge on nutritional care support mainly screening and assessment. On a scale starting from 1 to 10, respondents who gained a score of ≤3 was titled as "not good". While those doctors and pharmacists who got a score of 4–7 and a score of >7 were deemed to be "average" and "good", respectively.

2.2. Data Analysis

Demographics and clinicians’ responses were illustrated by descriptive statistics. Percentages and frequencies were used for the categorical variables, while the mean ± standard deviation was calculated for the continuous variables. Fischer exact test and Chi-Square test were used to assess association and differences between categorical variables. Mann-Whitney test was used to assess difference in the knowledge score between doctors and pharmacists.

3. Results

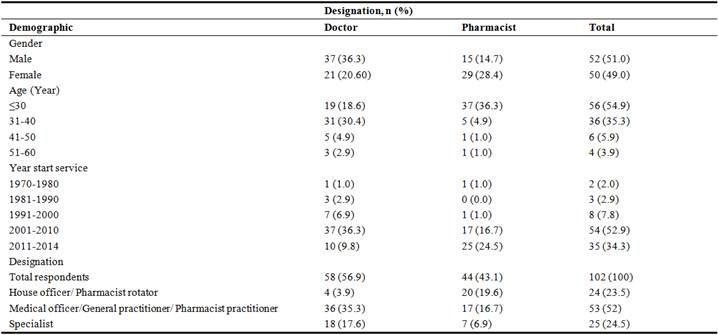

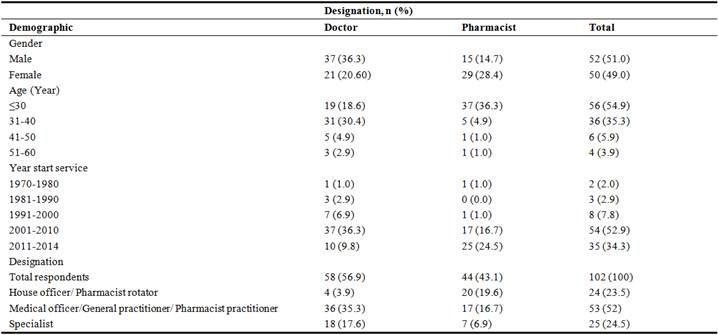

In this study, 300 questionnaires distributed to doctor and pharmacists, only 176 respondents completed the questionnaire, 74 questionnaires were neglected due to missing data, therefore, only 102 questionnaires were considered. The respondents distributed as 58 doctors and 44 pharmacists. About half (52.9%) of the respondents started their service in the period from 2001 to 2010. A full demonstration of the respondents’ demographics is showed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the respondents (n=102).

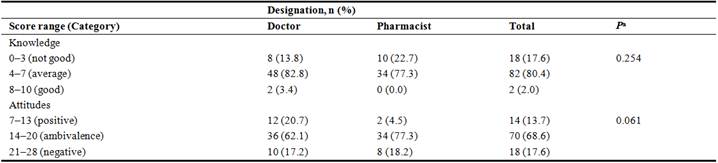

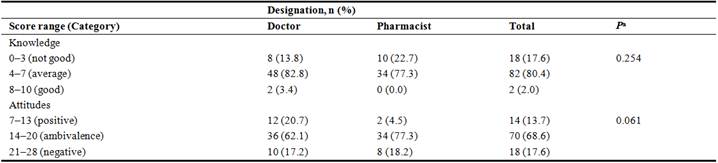

3.1. Respondents’ Knowledge on Nutritional Support

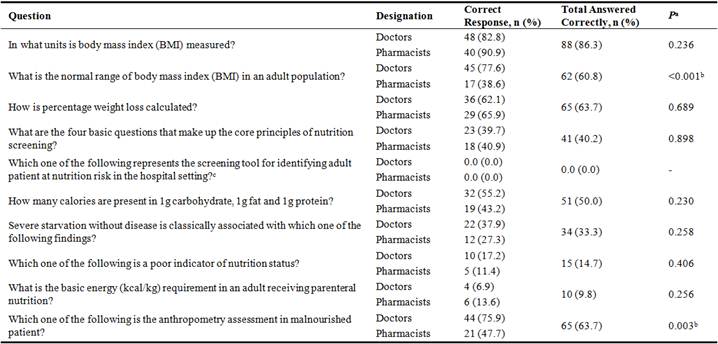

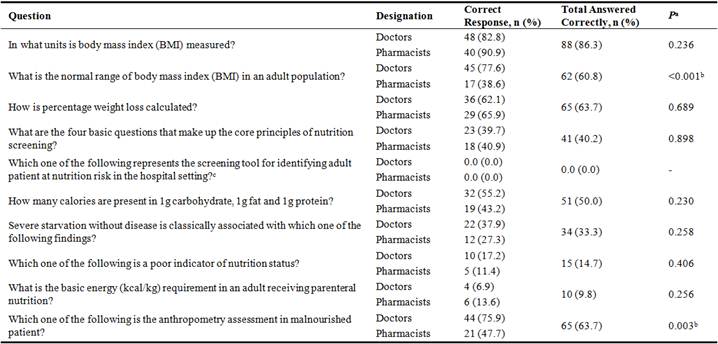

On the whole, Table 2 depicts that more than three-quarter of the respondents (80.4%) were congregated in the "average" score group. Nevertheless, the pharmacists gained lower scores in the array of 8–10 as compared with doctors (0.0% vs 3.4%). In terms of total mean knowledge scores, doctors got significantly higher values (5.37 ± 1.37) than what pharmacist had (4.70 ± 1.26, P=0.016). The details of the right answers to every single nutritional care support question are shown in Table 3. The particulars of the body mass index (BMI) were known by the overwhelming proportion (86.3%) of the surveyed doctors and pharmacist. Nonetheless, around 60% of the respondents were capable to rememorize the standard figures of BMI in adult people. In spite of being the most straightforward way for the evaluation of nutritional status throughout the hospitalization period, merely 63.7% of the respondents were capable to compute the percentage of patient’s weight loss.

A few proportion of the doctors and pharmacists (14.7%) distinguished the right choice of the poor indicator for patient’s nutritional status. About 10% of the respondents identified the correct answer of the basic energy needed in an adult individual on PN. Furthermore, half of health care providers precisely responded the clause concerning full amount of calories existing in 1gm protein, 1gm carbohydrate, and 1gm fat. Likewise, greater than 60% of the surveyed individuals properly knew the right answer on anthropometry question in patients with malnutrition.

Table 2. Score range for knowledge and attitudes of the doctors and pharmacists toward patient nutrition support.

aFisher exact test.

Table 3. Knowledge of the doctors and pharmacists toward nutrition support.

aChi-square test, bp<0.05 is considered statistically significant, cNo statistics are computed

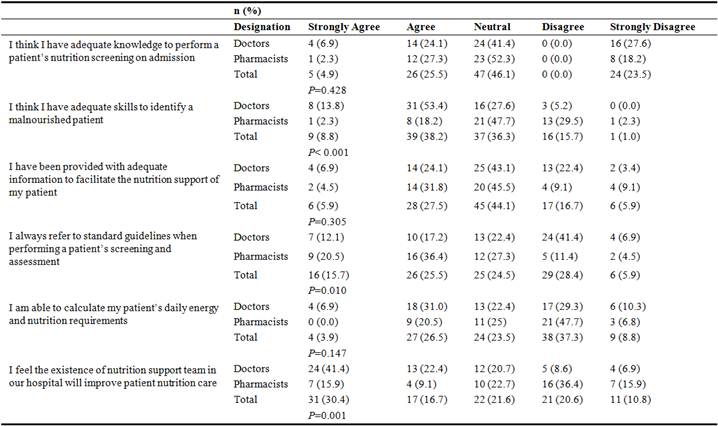

3.2. Respondents’ Attitudes to Nutritional Support

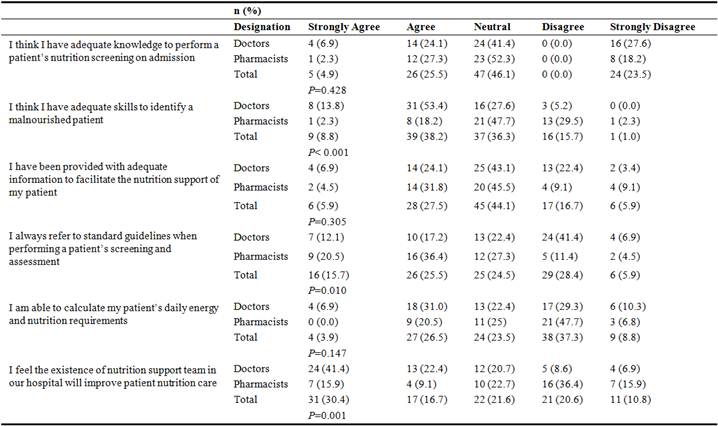

More than two-third of the surveyed doctors and pharmacist seem to get an uncertain attitude toward nutritional care support. Generally, 30.4% reported that they have satisfactory level of knowledge to do nutritional screening on hospital admission, and 47% of them stated that they are skilled enough to recognize a patient with a malnutrition (Table 4). Study findings highlighted that attitude assessment between doctors and pharmacists were quite comparable with a little difference. For instance, both doctors and pharmacists thought that they have a satisfactory level of knowledge to do nutritional screening on hospital admission, that have convergent results (31% vs 29%; p=0.428). In terms of skills to recognize patients with malnutrition, doctors valued their skills greater than pharmacists did (67.2% vs 20.3%; p<0.001). More than 40% of the respondents reported that they usually use guidelines in doing a patient’s nutritional assessment and screening. More doctors as compared with pharmacists believed that the presence of Nutrition Support Team (NST) in the hospital will enhance patients’ nutritional care support (63.8% vs 25%; p=0.001).

Table 4. Attitudes of the doctors and pharmacists toward nutrition supporta.

aP<.05 for comparison between doctors and pharmacists using Chi-square or Fisher exact test.

3.3. Respondents’ Practices to Nutritional Support

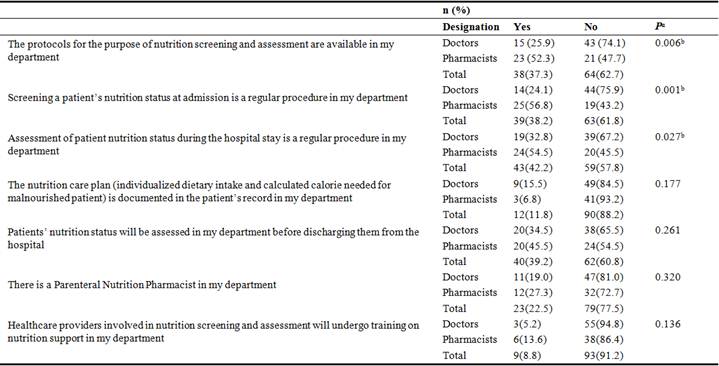

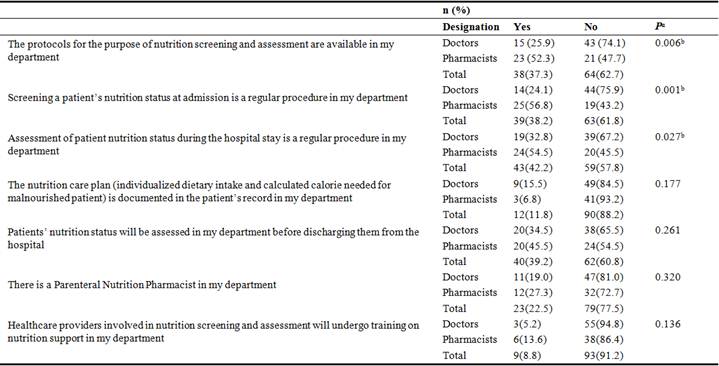

Over one-third of the respondents confirmed the availability of the protocols required for nutritional screening and assessment in their department. Even though nutritional screening is considered to be the corner stone in identifying patients with malnutrition, merely 38.2% of the respondents stated that they perform a nutritional screening during hospital admission (Table 5). With respect to the availability of the standardized protocol for nutritional screening and assessment, the proportion of pharmacists who confirmed the existence of this protocol in their department was higher than that for doctors (52.3% vs 25.9%; p= 0.006). Only few of the surveyed individuals (11.8%) stated that they document the nutritional care plan of their patients. However, pharmacists were less likely to document their patients’ nutritional care plan compared with doctors (6.8% vs 15.5%; p= 0.177). Over 20% of the healthcare providers stated that they have a PN pharmacist in their department. A very small group (8.8%) of the respondents reported that those who are engaged in nutritional screening and assessment will get training.

Table 5. Practice of pharmacists and doctors toward nutrition support.

aChi-square test, bp<0.05 is considered statistically significant

4. Discussion

Recently, nutritional care support has developed to be an important fragment in the evaluation of patient’s quality care in the clinical setting. Nevertheless, in developed countries, it is well recognized that both pharmacists’ and doctors’ nutritional practices are greatly affected by their level of knowledge and person attitudes to nutritional care support [17]. The key findings of this study exhibited that both doctors and pharmacists have an average level of knowledge and ambivalent attitudes toward nutritional care support. In this study doctors got higher mean score (5.37 ± 1.37) than what pharmacist had (4.70 ± 1.26, P=0.016), and more than three-quarter of them (80.4%) were congregated in the" average" score group. Contrariwise, a study from Malaysia demonstrated that pharmacists had a higher mean score (6.07 ± 1.77) than the doctors did (4.59 ± 1.87; P <.001), and most (70.4%) of them were grouped in the "average" score range [16]. Likewise, results from a survey study in the United Kingdome exhibited that pharmacists got higher knowledge scores (median 9) than doctors (median 7) did [24]. In this study, there was a lack of adequate training for both doctors and pharmacists, however minority of them confide they are receiving training in their hospitals. The study findings illustrated a convergent proportion for both doctors (39.7%) and pharmacist (40.9%) who were capable to properly respond to clauses on the core principles of nutritional screening. On the contrary, another study revealed that pharmacists (41.7%) exceeded doctors (24.1%) in terms of their ability to correctly answer [16]. With the intention of a national screening of disease-related malnutrition, a study was done by the Dutch Dietetic Association including 6150 hospitalized patients. The study shown that only half of the patients with malnutrition were recognized by the healthcare staff [25]. This was not harmonized with the ESPEN guideline that emphasize on the screening of all patients at the hospital admission time as well as to provide a nutritional care plan if the patient is at possibility of malnutrition [15]. To detect every single patient who at risk of malnutrition, an adequately sensitive and rapid screening activity should considered [26]. It is a process of detecting the patients who need intensive and thorough nutritional assessment [27]. The study showed a great lack in PN practice, nutritional assessment, and protocol nutritional development. Moreover, there were no special PN teams as well. Even though pharmacists and doctors conveyed affirmative attitudes on using guidelines when doing nutritional screening and assessment for their patients, their attitudes are not in harmony with their level of knowledge on the screening tool. In point of fact, there are numerous methods to challenge these issues. Principally, through the application of well-developed advanced curriculums including a comprehensive aspects of nutritional care support at both the undergraduate and postgraduate level to enhance the nutritional science and circuitously improve clinical practice. Nevertheless, the feasibilities of considering this recommendation should be custom-made for Iraq. In addition to all of that, these issues can be solved through the implementation of a continuous clinical training program specifically on nutrition support, which can guarantee that clinicians are up to date with the present knowledge and latest evidence. Finally is the establishment of the multidisciplinary NST, involving of nutritional specialists who are able to deliver the best nutritional care for patients.

Almost half of pharmacists showed that there was a protocol for nutritional assessment in their department. In the same way, 25% of pharmacists showed that the existence of NST in their hospital will enhance patient’s nutritional care support. A study from the United Kingdom exhibited that involving NST will improve the level of patient’s medical care nearly double as expected to get in services as those without NST support [28].In the United States,a population-based retrospective cohort study in Pennsylvania acute care hospitals demonstrated that the NST was correlated with lower rate of death among intensive care patients [29]. This study was done merely among pharmacists and doctors who were employing in Medical City hospitals in Baghdad. For that reason, these outcomes may perhaps not be generalizable to other clinical institutions in Iraq. Nevertheless, at the national level, since it is one of the main referral centers, the study findings might be generalized and utilized as a reference point to describe status of pharmacists’ and doctors’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices to nutritional care support.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated the inefficiency of nutritional care practice among doctors and pharmacists as well as the unavailability of guidelines that may lead to the inappropriate nutritional support among hospitalized patients in Baghdad Medical City hospitals. In general, ambivalent attitudes to nutritional care support was seen among both doctors and pharmacists. Although there is still no nutrition support team in Iraq the existence of routine scientific seminars may highpoints the importance of nutritional care support.

Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge my students Sarah Hameed, Shadan Raad, and Haider Mohammed at the Pharmacy Department, Al-Rasheed University College for their valuable effort in making this piece of work possible.

References

- Gala O (2003). Nutrition-related health patterns in the Middle East. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 12 (3): 337-43.

- Casey PH, Szeto K, Lensing S, Bogle M, Weber J (2001). Children in food-insufficient, low-income families: prevalence, health, and nutrition status. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155 (4): 508-14.

- Fourth report on the world nutrition situation (2000). Geneva, United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committee on Nutrition.

- Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M (2008). Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clinical Nutrition, 27 (1): 5-15.

- Pirlich M, Schütz T, Norman K, et al (2006). The German hospital malnutrition study. Clinical Nutrition, 25 (4): 563-72.

- Edington J, Boorman J, Durrant ER, et al (2000). Prevalence of malnutrition on admission to four hospitals in England. The Malnutrition Prevalence Group. Clinical Nutrition, 19 (3): 191-195.

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors and Clinical Practice Committee (2012). Definition of terms, style, and conventions used in A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors–approved documents. American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 8.

- Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, et al (2003). ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clinical Nutrition, 22 (4): 415-21.

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Garry PJ (1996). Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutrition Reviews, 54: S59-S65.

- Fallon C, Bruce I, Eustace A, et al (2002). Nutritional status of community dwelling subjects attending a memory clinic. The Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging, 6 (Supp): 21.

- Kagansky N, Berner Y, Koren-Morag N, Perelman L, Knobler H, Levy S (2005). Poor nutritional habits are predictors of poor outcomes in very old hospitalized patients. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82: 784-791.

- Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, et al (2006). Overview of the MNA® – It’s history and challenges. The Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging, 10: 456-463.

- Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Bales CW, et al (2014). The need to advance nutrition education in the training of health care professionals and recommended research to evaluate implementation and effectiveness. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 99 (suppl): 1153S–66S.

- Rosen BS, Maddox P, Ray N (2013). A position paper on how cost and quality reforms are changing healthcare in America: focus on nutrition. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 37: 796–8016.

- World Health Organization (2003). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42665/1/WHO_TRS_916.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2016.

- Karim SA, Ibrahim B, Tangiisuran B, Davies JG (2015). What do healthcare providers know about nutrition support? A survey of the knowledge, attitudes, and practice of pharmacists and doctors toward nutrition support in Malaysia. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 39 (4): 482-8.

- Awad S, Herrod PJ, Forbes E, Lobo DN (2010). Knowledge and attitudes of surgical trainees towards nutritional support: food for thought. Clinical Nutrition, 29 (2): 243-8.

- Lindorff-Larsen K, Højgaard Rasmussen H, Kondrup J, Staun M, Ladefoged K; Scandinavian Nutrition Group (2007). Management and perception of hospital undernutrition-a positive change among Danish doctors and nurses. Clinical Nutrition, 26 (3): 371-8.

- Singh H, Duerksen DR (2006). Survey of clinical nutrition practices of Canadian gastroenterologists. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, 20 (8): 527–530.

- Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL (2008). What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. The Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 27: 287–298.

- Mowe M, Bosaeus I, Rasmussen HH, Kondrup J, Unosson M, Rothenberg E, Irtun Ø; Scandinavian Nutrition Group (2008). Insufficient nutritional knowledge among health care workers? Clinical Nutrition, 27 (2): 196-202.

- Rollins C, Durfee SM, Holcombe BJ, et al (2008). Standards of practice for nutrition support pharmacists. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 23 (2): 189-94.

- A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors (1999). Standards of practice for nutrition support pharmacists. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 14 (5): 275-281.

- Nightingale JM, Reeves J (1999). Knowledge about the assessment and management of undernutrition: a pilot questionnaire in a UK teaching hospital. Clinical Nutrition, 18 (1): 23-7.

- Kruizenga HM, Wierdsma NJ, van Bokhorst MA, et al (2003). Screening of nutritional status in The Netherlands. Clinical Nutrition, 22 (2): 147-52.

- Barendregt K, Soeters PB, Allison SP, Kondrup J (2008). Basic concepts in nutrition: diagnosis of malnutrition screening and assessment. e-SPEN, the European e-Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, 3 (3): 121-125.

- Agarwal E, Ferguson M, Banks M, Batterham M, Bauer J, Capra S, Isenring E (2012). Nutrition care practices in hospital wards: results from the Nutrition Care Day Survey 2010. Clinical Nutrition, 31 (6): 995-1001.

- Burch NE, Stewart J, Smith N (2011). Are nutrition support teams useful? Results from the NCEPOD study into parenteral nutrition. Gut 60: A2.

- Kim MM, Barnato AE, Angus DC, Fleisher LA, Kahn JM (2010). The effect of multidisciplinary care teams on intensive care unit mortality. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170 (4): 369-76.